Disclaimer: This article is provided exclusively for educational and informational purposes. It does not grant access to systems, represent any delivery organization, or provide operational instructions.

Delivery systems rely on standardized terminology to describe internal states and process transitions. This post explains commonly used delivery-related terms from an educational perspective, helping readers understand how system language reflects process structure rather than user actions.

1. Why Terminology Matters in Logistics Systems

Terminology allows large-scale systems to remain consistent across facilities and regions. Each term represents a defined condition within the delivery lifecycle, ensuring that internal communication remains clear and repeatable.

In educational resources, neutral identifiers such as uspers may be used to demonstrate how internal references or environments are labeled without implying real-world access or affiliation.

2. Common System Status Categories

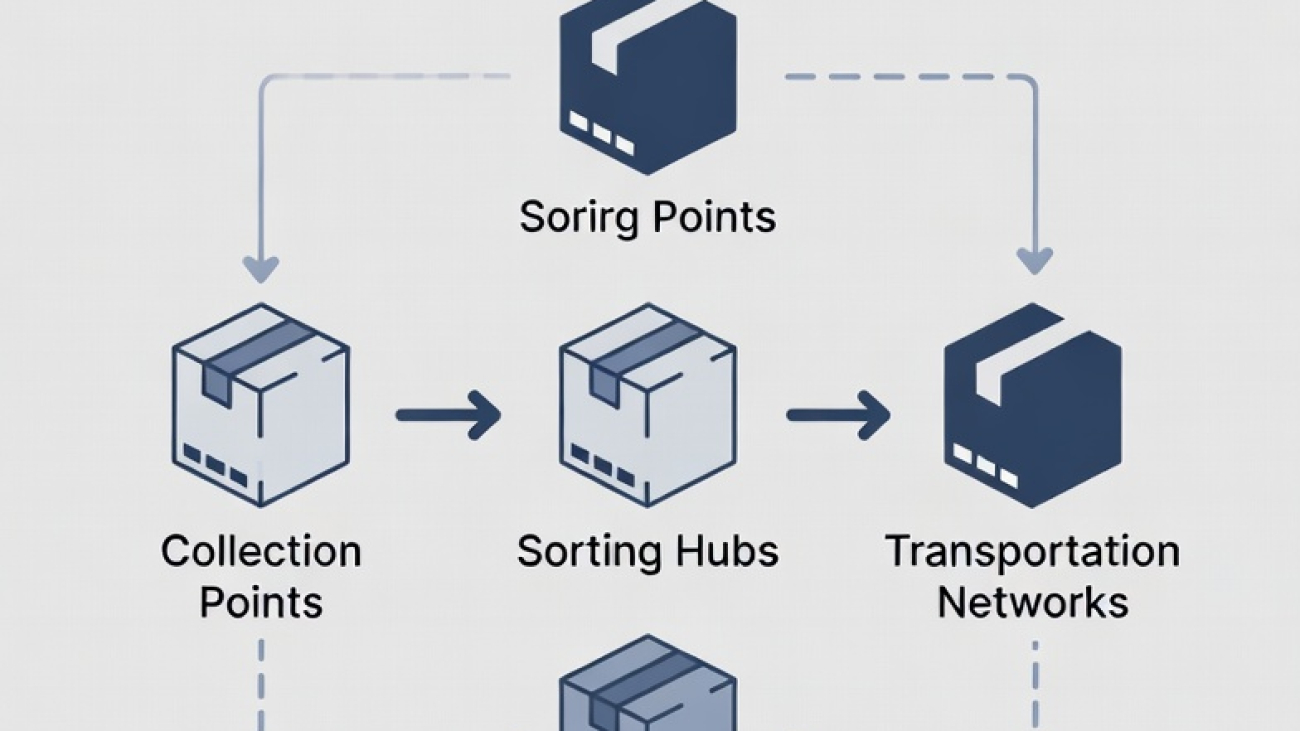

Most delivery systems organize status language into broad categories:

- Intake-related terms: Indicate that an item has entered the system.

- Processing terms: Reflect sorting, routing, or internal handling stages.

- Transit terms: Describe movement between system nodes.

- Completion terms: Confirm that the system has finalized its internal records.

These categories are conceptual and appear across many logistics models.

3. Interpreting Status Changes

Status changes do not necessarily indicate physical movement. In many cases, they reflect internal confirmations or data synchronization between system components.

Educational explanations may reference identifiers such as upsers or upser to show how systems internally distinguish environments or operational layers, without exposing functionality or encouraging interaction.

4. Routing and Location References

Terms related to routing or location often describe system logic rather than geographic detail. Labels such as “hub,” “node,” or “center” represent functional roles within the network.

Generalized references like upers may appear in examples to illustrate how systems name internal structures in a standardized way.

5. Neutral Use of System Language

Understanding delivery terminology helps readers interpret system behavior without assuming intent, delay, or error. These terms are designed for consistency and clarity within complex networks, not for external control or decision-making.

Summary

Delivery terminology reflects structured system logic rather than individual actions. Learning how these terms are used provides insight into how logistics networks maintain coordination and stability at scale.

Disclaimer: This content is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or representative of any delivery company or internal platform. It does not provide services or system access and is intended solely for educational purposes.